Welcome back to Reality Test! I spent last week scrolling TikTok for the newsletter so this week it felt right to read some studies. As always, send thoughts, ideas and feedback my way. I appreciate you!

Earlier this week, Fast Company published The Hidden Reason Why Therapy Isn't Working – the so-called “hidden” reason being that many clients are matched with the wrong therapist, whether it’s due to the wrong intervention or a lack of skill.

The article was written by the founder of a company that staffs a great number of therapists and boasts a matching process more thorough than its competitors (read: BetterHelp). Though the piece is essentially an ad for his business, the founder makes a compelling case for therapists to measure outcomes more effectively. The author writes that most therapists do not use empirical measurement to track results, such as standardized assessments like the GAD-7 for anxiety and the PHQ-9 for depression, and that this would be unacceptable in any other medical profession.

Fair. This newsletter has, several times, touched on the idea that just *going to therapy* is not something curative on its own. You need to be in the right therapy, with the right therapist and to actually engage with the process to achieve the best results. The founder also reminds us that therapy should be leading to an end point when the client has reached their goals and/or is no longer benefiting from therapy, which is a philosophy I agree with (as does my Code of Ethics).

However, I believe the reality of how we work toward positive therapeutic outcomes is a bit more complicated. Having therapists who are more skilled using interventions that are more effective is a great goal. However, our systems of measurement and training are highly subjective and flawed, which leaves us needing to accept a messier (and arguably, more human) reality.

Clinical competence – having adequate knowledge and training to practice – is a surprisingly vague concept. It’s defined by the National Association of Social Workers as the ability to practice within one’s area of expertise while continuing to pursue new knowledge. Ok. So how do we quantify knowledge and expertise?

There are a few ways for licensed clinicians to increase competence in a certain therapeutic modality or intervention. You can attend trainings, seminars, read books, seek supervision. For the most part, none of these things on their own will get you a certification in whatever you’re studying – that is, an official endorsement from a professional organization or training school that essentially says “yes, this person trained with us in our method,” represented by some letters you can put next to your name.

An example: Most clinicians know the basics of Cognitive Behavior Therapy (CBT), learned about it in school, even use elements of it in their practice. However, official certification in CBT from the Beck Institute looks like this:

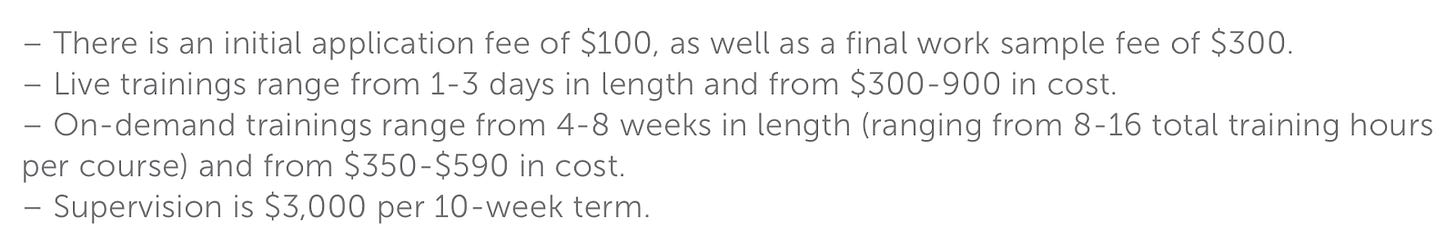

So if you see someone listed with these letters next to their name, you know for sure that this person has completed a number of required CBT courses, received a certain number of supervised clinical hours, and been evaluated by a board of CBT experts. It also indicates membership to a professional organization. The website says it takes on average 1-2 years to complete accreditation. You can also take one-off training classes through the Institute and receive a certificate of completion for that course only. Here’s what the FAQs say on the question of cost for each required piece of the certification program:

So you can imagine why most people don’t do this.

All this said, you can have basic clinical competency in CBT without doing any of these things. My guess is that this is the case for most clinicians. For example, many of my clinical courses in grad school focused on CBT. I wrote papers, did role plays, gave presentations on it. I’m not going to tell you this in my therapist bio. I will, however, use elements of CBT in my practice when appropriate. I’ve decided my clinical competence is adequate in order to draw from CBT in session when it feels right. Though this is clearly imperfect, the stark alternative – getting accreditation in a modality I’m not all that invested in on the whole – is not so appealing or accessible to me.

Then there’s the issue of the efficacy of the therapy itself.

Evidence-based therapy, that is, psychological interventions supported by empirical research (CBT being the classic example), is the gold standard for treatment of mental diagnoses (particularly to get insurance coverage) yet is still somewhat controversial. A 2019 meta-analysis of evidence-based treatments showed low replicability, even some fraud in reporting, and overall just largely disappointing results for some of the evidence-based treatments that we use as standard-bearers. There is also evidence of racial bias in the process of developing and measuring these therapies.

In an accompanying article on their results, the authors of the 2019 study wrote:

“The other conclusion is a lesson in humility for those who provide therapy (one of the authors of this article among them). For close to a century, psychologists have debated the ‘dodo bird hypothesis’. Deriving its name from the proclamation of the Dodo Bird in Alice in Wonderland (‘Everybody has won and all must have prizes!’), the dodo bird hypothesis suggests that different forms of psychotherapy perform equally well, and that this is because of the common factors of all therapies (eg, they all provide clients with a rationale for the therapy). The existence of ESTs [empirically substantiated treatments] seems to refute the hypothesis, demonstrating that some therapies do work better than others for certain mental-health conditions. We put forward a different possibility: the ‘don’t know’ bird hypothesis. Given the problems with credibility we found across many clinical trials, we contend that we currently don’t know in many cases if some therapies perform better than others. Of course, this also means we don’t know if the majority of therapies are equally effective, and, if such equality exists, we don’t know if it owes to common factors. When it comes to comparing psychotherapies, therapists could do worse than to channel every philosophy undergrad: when someone purports one therapy works better than another, wonder aloud: ‘How do we know?’”

Somewhat unsatisfyingly, sometimes the answer is that we can’t know that much for certain. It’s an uncomfortable truth.

I write all this just to add some color to Fast Company’s assertion that if we just use more measurement, more standardized modes of training, then we will see better outcomes across the board. He writes, “Given the mental health crisis we face in this country, it’s time to insist on a higher standard for the most efficacious tool we have in outpatient mental health.” I agree, but I’m still left wondering how.

I’m privileged to have a great supervisor and thoughtful, skilled colleagues. When it comes to clinical competence, though, I am ultimately responsible for moderating it myself. I’m always going to have some bias, whether it leans more toward impostor syndrome or toward overconfidence. Similarly, a client will always have some bias as to whether they are seeing improvements in their lives as a direct result of therapy. Training programs and standardized assessments are a useful tool, but they have limits.

Take one of the standardized assessments cited in the article, the GAD-7, widely used to measure anxiety. Here’s the whole questionnaire:

There is certainly a place for empirical measurement like this, and it’s important to know how your symptoms evolve, and hopefully decrease, over time. But think of all the other factors that could influence your answers here on either side. Has a loved one recently been diagnosed with something? Did you just start taking Ozempic? Is there an election of great and terrifying national importance in 4 weeks? Did you just start going to yoga? Have you recently come into money?

And maybe even more importantly, how are your relationships? How’s your self esteem? How bothered are you still by that thing that happened with an old friend 5 years ago? Do you feel seen and understood by this survey?

So where does that leave us? Using the principle of both/and, I posit: Measurement is important, AND it’s not the only thing.

When you train as a musician, you practice technique over and over so that once you’re in performance, the technique is ingrained in your body such that creative expression can take control. I see it similarly with therapeutic training. When I’m in session, I have an ambient awareness of the theories and the practices that guide my work but my focus is on what’s happening with the client right in front of me. That’s what I am responding to.

We’re in the business of human emotions, and there’s no getting around the fact that that is MESSY AS HELL. We need research, supervision, clinical training, and accreditation. We need institutions to support us. But the institutions alone can’t guarantee success. We have to accept that there is a part of this process that is deeply human, thus immeasurable. At the end of the day, it’s just you and me in the room.

Several people sent me this

Thanks for reading! Reality Test supports me spiritually, intellectually, and creatively. If you find it valuable, please consider a paid subscription so it can help support me monetarily, too. And if you or someone you know is looking for your own emotional support white girl with a masters degree, well, my books are open.